Non-equilibrium reweighting

Equilibrium reweighting from information theory

Consider a coordinate

Now let’s add some constraints.

First we will enforce all probabilities to be normalized

Working in the canonical ensemble, we add a constraint on the average energy,

The expression lends itself to equilibrium reweighting: sampling of

Reweighting of nonequilibrium steady-state dynamics

This formalism can be extended to nonequilibrium steady-state (NESS) dynamics. Moving from equilibrium thermodynamics to dynamics leads to the consideration of microtrajectories. Compared to microstates, their number quickly becomes intractable for all but the simplest of systems. For simplicity, we assume Markovian dynamics, so that we chop microtrajectories into bits that we can combine together. Effectively it converts an integral over a space-time trajectory into a sum

The discretized version of the cross-entropy functional becomes

Let’s add some constraints!

Ok, so there are different types of constraints we could include, but here we’ll only deal with microscopic ones. If we were in equilibrium, we’d be working with detailed balance,

Crooks fluctuation theorem

The Crooks fluctuation theorem weighs the probability of observing a trajectory under an external driving force against its time-reversed analog. Let’s denote the probability of observing the time-forward trajectory by

The expression for the local entropy production can be inserted as a constraint on the transition probability matrix elements to the cross-entropy functional (Eq. 2). We proposed such a functional in [Bause et al.][1], using such an approach for local balance, as well as a looser global balance constraint.

The resulting equation can be solved analytically, and its coefficients determined numerically by self-iteration.

Seifert expression for the local entropy production

One exciting aspect of Eq. (3) is the possibility to determine

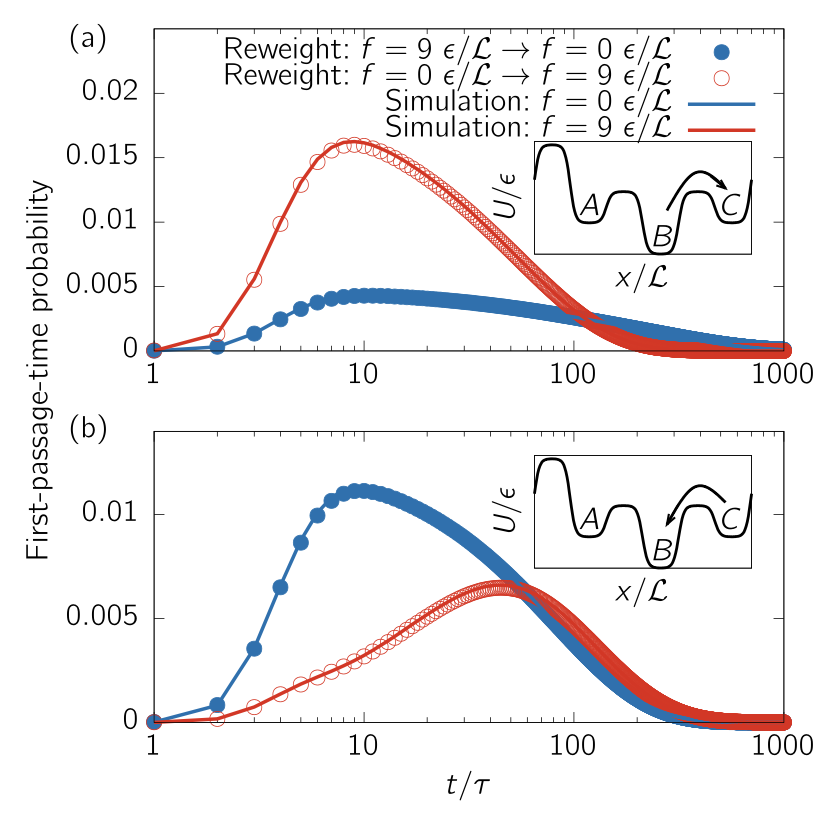

Marius Bause (first author in the paper) shows that the cross-entropy (aka Maximum Caliber) functional yields quantitative reweighting for overdamped Brownian dynamics. Here’s a comparison of reweighting in and out of equilibrium against direct simulations (take away: the points are on the top of the curves!):

His work leads to the formulation of an invariant. Just like the density of states, which does not change under change in temperature, this invariant does not depend on the driving force. It does, however, depend on the control variable (temperature of

Collective variables

Marius’ follow-up work demonstrates the applicability of the method to larger systems by working with collective variables. The trick consists of replacing the potential energy that is hidden in Eq. (4) by a potential of mean force. In analogy, think of how structure-based coarse-graining goes from an atomistic potential energy surface to a smaller potential of mean force. The derivation of local entropy production in collective coordinates can be found in [Bause & Bereau][2]. It allowed Marius to perform quantitative non-equilibrium reweighting for a small peptide.